Harry Hay and John Burnside were partners and the fathers of the Radical Faerie movement.

Harry Hay

The Father of the Radical Faeries

| “Confronted with the loving-sharing Consensus of subject-SUBJECT relationships all Authoritarianism must vanish. The Fairy Family Circle, co-joined in the shared vision of non-possessive love — which is the granting to any other and all others that total space wherein each may grow and soar to his own freely-selected, full potential — reaching out to one another subject-to-SUBJECT, becomes for the first time in history the true working model of a Sharing Consensus!” — Harry Hay, Arizona, 1979 |

| “The Hausa people of West Africa say that the men and women of the village who relate to each other have, each one, an eye in their soul by which they perceive themselves, however dimly, on the right path in the dark and perilous realm of SPIRIT. But the souls of those men among them who relate to other men, and women who relate to other women, have two eyes! This Two-Eyes feature, different from the way Eurocentric Imperialisms might misinterpret it, bestows neither special powers or privileges — instead it lays upon the Two-Eyed ones a sacred responsibility. For Two-Eyed ones have the capacity of vision to penetrate the dread gloom of the SPIRIT world to discern the path that their Group, their Community should follow to discover the next resting place, where they all will be temporarily safe and nurtured, on the SPIRIT journey all must take.” — Harry Hay, San Francisco, 1991 |

Remembering Harry

Harry Hay passed peacefully in his sleep at 2am on October 24, 2002, with a waxing full moon in Gemini. His partner John Burnside and longtime friend Joey Cain were with him when he died.

Please hold the Dutchess in your thoughts, throw glitter, be real with someone, kiss a man in public, or jack off to help Harry have a good transition. She loved us very much, and we have much to thank the cantankerous old girl for…

It’s important to keep a record of people who remember Harry — or benefit from his work. **Please send e-mail** to remember@radfae.org with your memory, anecdote, or Harry Hay story!

Remembering Harry and John

by Mark Thompson on the occasion of Harry’s 100th anniversary

There was no greater gay activist (and never will be, in my view) than Harry Hay. He took profound risks throughout a long and distinguished life, which has been amply documented in The Trouble with Harry Hay, a biography by Stuart Timmons, Radically Gay, a collection of his writings edited by Will Roscoe, and Hope Along the Wind, a film by Eric Slade. No greater risk taken was the day he declared his love for a modest and married man, John Burnside, back when such things were seldom publicly done. The proposal was accepted, and few gay romances have been as legendary. I was privileged to witness this relationship, and the effect it had on others, during the last two decades of their remarkable life together.

The first thing Harry Hay ever told me was to pull off my ugly green frog skin of heterosexual conformity. It was May Day, 1979, and I had just left a plane from San Francisco, where gay people danced naked in the streets. There wasn’t too much hetero-imitative behavior as far as I could see. And as for that ugly green frog suit, well, perhaps only as a really bad piece of drag.

Who was this character? A gay father figure with an overly active imagination? Or some kind of queer sage, a little too bent to fully comprehend? I decided to keep on listening. And I am so glad I did.

Hay and I met that afternoon in a small apartment near the Hollywood Hills to discuss upcoming plans for the first-ever Spiritual Conference for Radical Faeries. Nobody quite knew what a “radical faerie” was (including, I’m convinced, the organizers of the gathering). Yet it sure sounded grand, even romantic enough to capture the attention of readers. It did. Nearly two hundred gay men from across North America arrived at a remote Arizona oasis by summer’s end, kick-starting an international movement that flourishes to this day.

“Pardon me,” the voice asked with a soft tap on my bare shoulder. “But would you care for some more mud?” It was Harry’s life partner, John Burnside, and we were standing in a shallow ravine with fifty other naked men all covered with reddish wet earth and bits of chaparral in our hair. The mud ritual happened on the second day of the gathering and it was John’s job to make sure there was enough mud for everyone.

He wasn’t just offering a bucket of sandy ooze–but as much gay love and freedom from inhibitions that one could possibly tolerate in a summer day. That was John’s supreme calling in life: to liberate gay men from doubt and self-hatred, and thus hopefully inspire others to do the same. A perpetual smile, an impish wit, and curiosity about everything–especially other people–were the tools he employed (including dabs of mud) his entire life.

In the nearly thirty years I knew John, I never once heard a mean word from him. Oh, he might scold a tad if you did something dumb and he certainly enjoyed a lively debate. But John epitomized the full meaning of the word gentleman. While he relished being a sissy, he was no man’s fool and knew it. John was smart, funny, and considerate of others. He was also profoundly, at his very core, a gentle man.

John met Harry in 1963 at a gay community event in downtown Los Angeles. He was married with no children and divorced his wife. Harry had already done the same, leaving his troubled marriage and two daughters some years before. For them, it was love at first sight, an inspiring union that would last the next thirty-nine years. Soon they became one of the best-known gay couples in America; highly visible activists long before it felt safe or fashionable to do so.

They were widely interviewed in the media, and publicly stood up for a wide-range of progressive causes, seeing the struggle for gay civil rights as part of a wider movement for social change and justice. While Harry was the more vocal of the pair, John played an invaluable role as consort and mediator. He was their bedrock, a lifeline for calm and propriety in everything they did. What a beautiful balancing act it was.

Grand and romantic. Those are the two words that perfectly capture Harry’s essence. Except for some references in works by scholars Jonathan Ned Katz and John D’Emilio, not much was known in the late Seventies about the founder of the modern gay liberation movement. Time and better-publicized figures had passed him by. Harry and John had been out of sight living on pueblo Indian land in New Mexico during the previous decade. But the renewed call for a more inward kind of gay activism now pulled Harry back into the public’s eye, where he stayed for the next two decades with John at his side.

Harry loved to talk, and could expound eloquently on just about any topic. He hadn’t been nicknamed “The Dowager” for nothing back in the Thirties when he was introduced to the Communist Party by actor-boyfriend Will Geer. From the origins of democracy to fashion, Harry covered the conversational waterfront. (One of his many cohorts had been topless swimsuit inventor Rudi Gernreich.) Nothing escaped his attention, particularly if it informed his theories about gay consciousness.

His central idea–as revolutionary then as now–is that gay people have a special role to play in human evolution. He was the first to insist that we are a separate, distinct minority with certain traits and talents, mainly in the areas of teaching, healing, mediating opposites, and creating beauty. Harry’s notion or “call” as he put it, seemed fuzzy to a lot of people, especially those unable to differentiate between different and special.

As Harry made clear–no more painstakingly than over long hours at his kitchen table–being different meant “neither better nor inferior–but athwart.” He loved using five-dollar words like that. What he was basically saying is that the “gay window”–our unique and often deeply ironic way of seeing–has something essentially wonderful to offer humanity.

While both men shared similar politics and philosophy about gay life, they each had their own interests. Harry was a life-long scholar of indigenous peoples’ music and John was a creative inventor. A trained scientist, John had a special interest in optical engineering and created a new kind of kaleidoscope that used lens rather than glass chips to make a colorful design. By the Seventies, he had perfected his invention into a machine he called the Symetricon, which projected iridescent patterns of light.

The device was used in a number of Hollywood movies, but the best shows were the ones he gave at home on Saturday nights. There was always a sweet flock of faerie-identified men present for a simple vegetarian dinner. Then after the last dish was washed and put away, John would unfold his one-of-a-kind contraption while the rest of us snuggled on the floor in each other’s arms. The lights were dimmed, and off we all went on the most extraordinary ride over the rainbow anyone could imagine.

It could have been a cozy scene from the cover of an old magazine like The Saturday Evening Post, only considerably queered. John would work the gears and levers, making the shapes take incredible form, giggling like the fey wizard he was. If you’re going to call yourself gay, well then be truly gay, John said. A man always true to his word, I’ve never met a kinder or gayer fellow, much beloved by all who knew him.

For all his own considerable charm, Harry was sometimes pompous and irritatingly obtuse. After an hour or two of heady declamation, one just had to take a breather. At times like these, his headstrong Scottish heritage was obvious. Yet he too had a sly sense of humor–mixing anecdotes and allusions with as much savvy as he did his wardrobe. Who else but Harry could pull off pearls and a pink taffeta skirt worn over jeans and dusty work boots?

I remember the night we were socializing at the San Francisco Art Institute at a gala tribute for James Broughton. Harry and James had sparked briefly as Stanford University undergraduates, but didn’t meet again until fifty years later at a faerie gathering. Few people knew that James had fathered a daughter with esteemed film critic Pauline Kael during their bohemian Berkeley days, but Harry was alert to the fact. Kael and Broughton were having their own reunion at the moment when, with typical impudence, Harry interrupted the conversation by loudly asking, “So, who was the mother and who was the father?” The stunned silence was punctured only by the whoosh of Kael’s furious departure.

Harry was always giddying me, too–to loosen up, to see the bigger picture, to just be my total, fabulous, faerie self. I recorded many hours of conversation with him over the years and took dozens of photographs as well. My favorite happened at the end of a glorious August day, sitting together in an Oregon pasture where a faerie sanctuary had been established. Harry was on a didactical roll, explaining in vivid detail how he and a small band of very brave brothers had started the Mattachine Society in 1950 in Los Angeles–the first ongoing gay organization in the country.

I didn’t want to interrupt, even though the burr beneath the thin sarong separating my behind from the dirt was really beginning to hurt. I held my camera ready until the perfect moment came. “’Tis a gift to be gay,” he said, beaming, “and, honey, don’t you ever forget it.” In the photo, he looks angelically backlit. The glow came from deep within.

Harry Hay died on October 24, 2002, at age ninety. It was observed that he was not just a notable man of the year–but a man of the century. However, some wondered which century. The late Nineteenth, because of his philosophical ties with seminal thinkers of that era such as Walt Whitman and British writer Edward Carpenter? Or the Twentieth because of his fierce commitment to social justice and change? Or perhaps the one we’re in now, when the progress for gay civil rights is being widely enjoyed yet more profound understandings remain an enigma?

As far as I’m concerned, all of the above. Harry belongs in a core place beyond the margins–a balancing act he singly perfected. Of all the contrary individuals I’ve met in the gay movement, he possessed the one original true gay heart. A heartbeat, a voice, and a burr of conscience I continue to gratefully hear.

His trusted soul mate of four decades died six years later at age ninety-one, on September 14, 2008. Like Harry, radical faerie comrades surrounded John during his final days. Such a “circle of loving companions” had been their life-long dream, and so it came true. The legacy of their love will last for as long as such things are remembered and told. Without a doubt, the tale of Harry and John is one of the great gay love stories of all time.

Vito Russo interviews of Harry Hay & Barbara Gittings

Done in 1983. Part one, which contains most of the interview and the end in part two are posted below. They were posted by Richard Dworkin to You Tube.

Part one

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RSO5Y8fGac4

Part two

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6nRJhce0xe0&NR=1

Following is the obituary from the San Francisco Chronicle. It refers to the radical faeries as “his group” and says Harry never allowed women in. Fortunately, that isn’t quite what really happened, right girls?

San Francisco Chronicle

Harry Hay, gay rights pioneer, dies at 90

Thursday, October 24, 2002 Angela Watercutter, Associated Press Writer

(10-24) 20:54 PDT SAN FRANCISCO (AP) —

Harry Hay, a pioneering activist in the gay rights movement, died Thursday at 90. His family said he suffered from lung cancer.

Hay devoted his life to progressive politics and in 1950 founded a secret network of support groups for gays known as the Mattachine Society. He also was among the first to argue that gays had a cultural identity and could be discriminated against like any other minority group.

“What we haven’t been doing in the 20th century is discovering what we bring with us to contribute, which the United States needs, but doesn’t necessarily have,” Hay told The Associated Press in a recent interview. “Then our cultural minority appears in order to serve a purpose, instead of spending all our effort, time and money finding sex because it is the one thing that’s been denied to us.”

Hay was Born April 7, 1912, in Worthing, England. Family members said he was diagnosed several weeks ago with lung cancer, and he died peacefully in his sleep at his San Francisco home early Thursday morning.

Hay was a strong, articulate, forward-thinking presence, said his niece, Sally Hay. She formed a relationship with Hay in the 1990s, decades after the rest of the family had broken off contact because of his connection to the Communist Party in the 1930s.

“I have so much respect for his courage and his willingness to live his own life with integrity,” she said from her home in Providence, R.I. “I’m delighted that he lived long enough to have received the recognition he deserved.”

Hay was an actor living in Los Angeles in 1934 when he first became active in left-wing politics. He was involved in the labor movement of the 1930s and quickly realized he needed to organize the gay community.

“They weren’t gay, they weren’t a group, they were just those sissy guys. That was part of the social oppression then,” said Stuart Timmons, who published a biography of Hay in 1990. “You just didn’t dwell on those people and the idea that there might be a group of them. The idea they could be a minority, a constituency, a voting block, a market — all of those applications of putting a group identity onto gay people, that made all the difference.”

Hay formed the Mattachine Society in 1950. Based in Los Angeles, it was the first sustained homosexual rights organization in the United States.

But at the height of the investigations by the House Un-American Activities Committee, Mattachine members feared investigation. They decided to make the group public and purge it of any Communist influence — that included Hay.

Hay was called before the committee in 1955, but he refused to testify. The committee considered him insignificant and dismissed him.

Hay was a step ahead in 1969, when patrons at the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in New York’s Greenwich Village, clashed with police in an incident considered the birth of the modern gay rights movement.

“The importance of Stonewall is that it changed the pronoun from ‘I’ to ‘We,”‘ Hay told The AP. “When I told them at Stonewall that I had been thrown out of the Mattachine Society because I insisted that we were a cultural minority and not individuals, they couldn’t believe that. By the time of Stonewall they thought we had always been a cultural minority.”

Critics have accused Hay of limiting thinking within the gay rights movement. Some argue that women’s participation in the Mattachine Society was minimal and Hay has never allowed women into his group the Radical Fairies, which he started in 1979.

But Eric Slade, creator of the documentary, “Hope Along the Wind: The Life of Harry Hay,” said despite his stubbornness, Hay’s thinking never grew stagnant.

“He once told me, ‘Everyone, even heterosexual people, all have the potential to have that fairie spirit,”‘ Slade told The AP. “That was a big change for him.”

Hay is survived by his partner of 39 years, John Burnside, and his adopted daughters, Kate Berman and Hannah Muldaven.

Donations in his memory can be made to the San Francisco Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Community Center. No information on a memorial service was immediately available.

From the Boston Phoenix

The real Harry Hay

With his sometimes crackpot notions and radiant, ecstatic, vision of the holiness of being queer, Harry Hay refused to play the model homosexual hero

by Michael Bronski

EVEN IN THE GLOW of its conservatism, America — which was formed via revolution, after all — has always taken a certain pride in its radicals. Even so, America prefers to remember its history-makers in sanitized versions with none of the messy, often embarrassing flaws that are usually inscribed on the souls who take it upon themselves to change the world. Thus, we prefer to think of Thomas Jefferson as a revolutionary genius, rather than as slave owner who not only had sexual relations with his female slaves but consigned his own children to slavery. The fiery stances taken by anarchist and feminist Emma Goldman in the early part of this century are softened — or forgotten — in her incarnations as a grandmotherly figure in the film Reds and an innocuous witty commentator in the musical Ragtime. The popular image of Rosa Parks as a tired seamstress who just wanted a seat on the bus is far more comforting than the reality: she was a skilled political thinker and secretary of the NAACP chapter that planned the bus boycott long before she refused to sit down. Even the most serious biographers of Martin Luther King Jr. portray him in rosy hues, as an American saint, not as a deeply religious man whose promiscuity and adulterous behavior tore him apart.

So it is with Harry Hay — founder of the gay movement in America — who died at the age of 90 on October 24. Obits in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and the Associated Press left the impression that Hay was a passionate activist and something of a romantic. The New York Times referred to him as “an ardent American Communist, a romantic homosexual,” who was a “restless middle-aged man” by the time he formed the Mattachine Society, the first gay-rights group in the United States. The Los Angeles Times described Hay’s penchant for wearing “the knit cap of a macho longshoreman, a pigtail and a strand of pearls” and also noted that he and John Burnside, his lover of 40 years, lived most recently in San Francisco in a pink Victorian house.

The reality is that while Hay may have been a romantic, he was also notoriously promiscuous, and his communism was far more rabid than “ardent.” And while he did wear pearls with his longshoreman’s cap, it wasn’t a form of charming “gender-bender” chic, as the Los Angeles Times put it, but a political statement Hay first donned back when it was still quite dangerous to do so. Hay, in fact, was fanatically resistant to the grandfatherly image the modern gay movement not only tried to attribute to him but expected him to play out. The documentary Word Is Out, for instance, filmed in 1976, portrayed Hay and Burnside as paragons of gay domesticity. More recently, he was invited to address the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force’s Creating Change Conference, in 1998, and was billed as a major speaker. But he was given no context in which to talk about his politics and found himself treated more as an artifact of gay history than as an activist with ideas.

Hay had strong opinions and never pandered to popular opinion when he voiced them — whether he was attacking national gay organizations for what he saw as their increasingly conservative political positions (“The assimilationist movement is running us into the ground,” he told the San Francisco Chronicle in July 2000) or when he condemned the national gay press — in particular, the Advocate — for its emphasis on consumerism. He was, at times, a serious political embarrassment, as when he consistently advocated the inclusion of the North American Man/Boy Love Association (NAMBLA) in gay-pride parades.

HAY’S UNEASY relationship with the gay movement — he reviled what he saw as the movement’s propensity for selling out its fringe members for easy, and often illusory, respectability — didn’t develop later in life. It was there from the start. In 1950, when Hay formed the Mattachine Society — technically a “homophile group,” since the more aggressive idea of gay rights had yet to be conceived — his radical vision was captured in a manifesto he wrote stating boldly that gay people were not like heterosexuals. Indeed, Hay insisted, homosexuals formed a unique culture from which heterosexuals might learn a great deal. This notion was at decisive odds with the view put forth by many other Mattachine members: that homosexuals should not be discriminated against because gay people were just like straight people. By 1954, the group essentially ousted Hay.

It wasn’t the first time Hay had been booted out of a group he helped create. From the 1930s through the early 1950s, Hay had been an active member of the American Communist Party. In 1934, Hay and his lover Will Geer, who later played Grandpa on the long-running television series The Waltons, helped pull off an 83-day-long workers’ strike of the port of San Francisco. Though marred by violence, it was an organizing triumph, one that became a model for future union strikes — such as the one currently under way (but stymied by the Bush administration) at West Coast ports. During the 1940s, Hay struggled unsuccessfully to be honest about his homosexuality — of which he’d been certain since adolescence — while maintaining his status as a member of the Communist Party, which banned homosexuals from joining. He married a follow Communist Party member and adopted two daughters — even as he worked to form the Mattachine Society. But homophobia eventually won out. After the Mattachine Society gained notoriety in the early 1950s, Hay was unceremoniously kicked out of the Communist Party.>

The story of Harry Hay’s life was that he was always a just little too radical — and since he was also a bit of an egotist, too disinclined to demure — for the groups with which he was involved. He was also too idealistic. Hay took the name Mattachine from a secret medieval French society of unmarried men who wore masks during their rituals as forms of social protest. They, in turn, took their names from the Italian mattaccino, a court jester who was able to tell the truth to the king while wearing a mask. As an old-time socialist, he was drawn to communism because of its egalitarian vision and, in the late 1930s and early 1940s, its stand against fascism. But he was also an actor and a musician drawn to a brand of scholarship that romanticized popular culture as intrinsically progressive and revolutionary.

Despite, or perhaps because of, Hay’s difficulty getting along with others, his vision of gay liberation was decades ahead of its time. His monumentally important contribution to the gay movement was his ability to communicate the notion that homosexuals made up a cultural minority with its own history, political concerns, and organizational strengths. An often-told story about Hay (retold in the New York Times’ obituary) recounts how he came up with a political strategy in 1948 that no one had ever voiced before: giving votes in exchange for ideological support. To wit: identity politics for homosexuals — on the same model African-Americans had begun to use in organizations like the NAACP. Hay wondered — out loud, the most basic form of political organizing — if Vice-President Henry Wallace, who was the Progressive Party’s candidate for president, would back a sexual-privacy law if he could be assured that a majority of homosexuals would vote for him. The politics of quid pro quo was revolutionary for its time. Remember, at that time it was dangerous to publicly identify as a “homosexual” — you could be arrested merely on the suspicion that you might be looking for sex; many states legally forbade serving drinks to homosexuals, much less allowing homosexuals to gather together in public. Indeed, the American Psychological Association’s lifting of the definition of homosexuality as a mental illness was a good 20 years away.

That said, Hay’s vision was not completely original. It drew partially on the work of late-19th/early-20th-century gay British socialist Edward Carpenter and, to a lesser extent, the political work of Magus Hirschfeld. Carpenter pushed the idea that people with homosexual desires were a distinct group with a well-defined identity, and thus could have a distinctive consciousness about their place in society. Hay, who was born in England in 1912 and moved to the US with his parents almost 10 years later, would have had easy access to Carpenter’s ideas, which were popular through the 1920s. But even though Hay’s notions had roots in European intellectual circles, they were truly radical in American political thought.

Political genius that he was, Hay never would have achieved what he did without his training as an organizer for the American Communist Party. He used the party’s own “cell” organization to build and propagate the ever-growing Mattachine. Even the group’s recruitment tactic — it was as dangerous to walk up to someone and say, “Hey, are you a homosexual? Want to join our club?” as it was for someone to drum up membership for a seditious political group — was modeled on the Communist Party’s strategy of getting names of potential members from current members.

THE HOMOPHILE movement of the 1950s and 1960s gave way after the 1969 Stonewall riots to the Gay Liberation movement. With its roots in feminism, the Black Power movement, street culture, and the antiwar movement, the Gay Liberation movement initially appealed to Hay. It was, essentially, the movement he had envisioned in 1950 but that never came to fruition. Soon, however, Hay became disenchanted as the radical Gay Liberation movement became corporatized with groups like Gay Activist Alliance and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, whose goals were to assimilate into the mainstream rather than change the basic structures of society. Hay, yet again, was a queen without a movement.

During these years, Hay spoke out against what he saw as the increasing conservatism of the gay-and-lesbian movement. As he saw it, the gay — and now, lesbian — movement was far more interested in electing homosexuals to government positions than in making the government responsible to the needs of its people. It was more interested in making sure that gay people were represented in commercial television and films than in critiquing the ways mass culture destroyed the human spirit. It was too interested in making strategic alliances with conservative politicians, rather than exposing how most politicians were working hand in glove with bloodless, destructive corporations.

Hay’s response was to reinvent gay politics all over again: in 1979, he founded the Radical Faeries. The spiritual core of the Radical Faeries was the same as the one Hay had envisioned for his original Mattachine Society: the conviction that gay men were spiritually different from other people. They were more in touch with nature, bodily pleasure, and the true essence of human nature, which embraced both male and female. Hay’s spiritual radicalism had its roots in 17th-century British dissenting religious groups, such as the Diggers, Ranters, Quakers, and Levelers, who sought to refashion the world after their egalitarian, socialist, non-hierarchical, utopian views. Unlike his dissenting predecessors, however, it wasn’t millennial Christianity that drove Hay, but a belief that all sexuality was sacred. And a belief that queer sexuality had an essential outsider quality that made the outcast homosexual the perfect prophet for a heterosexual world lost in strict gender roles, enforced reproductive sexuality, and numbingly straitjacketed social personae. The Radical Faeries were something of a cross between born-again queers and in-your-face frontline shock troops practicing gender-fuck drag.

By this time, the gay movement — which had devolved from a “liberation” movement into a quest for “gay rights” — treated Hay as a benign crackpot. He was frequently praised as an important historical figure, but no one was really interested in what he had to say, especially since the Christian right had already begun to launch vicious anti-gay attacks with Anita Bryant ’s “Save Our Children” campaign of 1979 and California’s Briggs Initiative (which would have banned openly gay schoolteachers) a year later. Often the discomfort with Hay was coupled with an overriding discomfort with his long history of involvement with the American Communist Party. More often than not, though, his relationship with Will Geer was touted as proof that — just like Grandpa Walton — Hay was an icon of safe respectability.

Despite his 40-year relationship with John Burnside, the aging radical still proclaimed the joys of sexual promiscuity and denounced the increasingly popular mandate that monogamy was a preferable lifestyle. In his own determined, often irritating, manner, Harry Hay resisted becoming a model homosexual hero. Nowhere was this more evident than in Hay’s persistent support of NAMBLA’s right to march in gay-pride parades. In 1994, he refused to march with the official parade commemorating the Stonewall riots in New York because it refused NAMBLA a place in the event. Instead, he joined a competing march, dubbed The Spirit of Stonewall, which included NAMBLA as well as many of the original Gay Liberation Front members. Even many of Hay’ s more dedicated supporters could not side with him on this. But from Hay’s point of view, silencing any part of the movement because it was disliked or hated by mainstream culture was both a moral failing and a seriously mistaken political strategy. In Harry’s eyes, such a stance failed to grapple seriously with the reality that there would always be some aspect of the gay movement to which mainstream culture would object. By pretending the movement could be made presentable by eliminating a specific “objectionable” group — drag queens and leather people were the objects of similar purges in the 1970s and 1980s — gay leaders not only pandered to the idea of respectability but betrayed their own community.

In death, though, Harry Hay’s critics have finally been able to do what they couldn’t do when he was alive: make him presentable. The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force and the Human Rights Campaign have issued laudatory press releases. (The HRC’s Davis Smith says, for example, “When you were in a room with him, you had the sense you were in the company of a historic figure.” A sense I certainly didn’t get at a cocktail party 12 years ago, when he came across as nothing but a cantankerous old queen who was more interested in speculating about what some of the younger party guests would be like in bed than discussing the connections between 1950s communism and gay-community organizing.) Even the Metropolitan Community Church issued a statement hailing Harry Hay’s support for its work (a dubious idea at best). Neither of the long and laudatory obits in the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times mentioned his unyielding support for NAMBLA or even his deeply radical credentials and vision. Harry, it turns out, was a grandfatherly figure who had an affair with Grandpa Walton. But it’s important to remember Hay — with all his contradictions, his sometimes crackpot notions, and his radiant, ecstatic, vision of the holiness of being queer — as he lived. For in his death, Harry Hay is becoming everything he would have raged against.

By Stuart Timmons, Hay’s official biographer, historian Martin Duberman, Joey Cain of the San Francisco GLBT Pride Parade, and Harry Hay’s niece, Sally Hay:

Pioneer, coalition-builder and radical faerie

Nov. 2002

Henry “Harry” Hay, the founder of the modern American gay movement, died on October 24, 2002 at age 90. He had been diagnosed weeks earlier with lung cancer. Despite his illness, he remained lucid to the end and died peacefully in his sleep at his home in San Francisco.

“Harry Hay’s determined, visionary activism significantly lifted gays out of op-pression,” said Stuart Timmons, who published a biography of Hay, called “The Trouble with Harry Hay,” in 1990. “All gay people continue to benefit from his fierce affirmation of gays as a people.”

Hay devoted his entire life to progressive politics, and in 1950 founded a state-registered foundation network of support groups for gays known as the Mattachine Society.

Hay was also a co-founder, in 1979, of the Radical Faeries, a movement affirming gayness as a form of spiritual calling. A rare link between gay and progressive politics, Hay and his partner of 39 years, John Burnside, had lived in San Francisco for three years after a lifetime in Los Angeles. Hay is listed in histories of the American gay movement as the first person to apply the term “minority” to homosexuals. An uncompromising radical, he easily dismissed “the heteros” and never rested from challenging the status quo, including within the gay community.

“Harry was one of the first to realize that the dream of equality for our community could be attained through visibility and activism,” said David M. Smith of the Human Rights Campaign in Washington, DC. “When you were in a room with him, you had the sense you were in the company of a historic figure.”

Due to the pervasive homophobia of his times (it was illegal for more than two homosexuals to congregate in California during the 1950s), Hay and his colleagues took an oath of anonymity that lasted a quarter century until Jonathan Ned Katz interviewed Hay for the ground-breaking book “Gay American History,” published in 1976. Countless researchers subsequently sought him out. In recent years, Hay became the subject of a biography, a PBS-funded documentary, and an anthology of his own writings called “Radically Gay: Gay Liberation in the Words of Its Founder.”

Before the establishment of the Mattachine Society, attempts to create gay organizations in the United States had fizzled or been stamped out. Hay’s first organizational conception was a group he called Bachelors Anonymous, formed to both support and leverage the 1948 presidential candidacy of Progressive Party leader Henry Wallace. Hay wrote and discreetly circulated a prospectus calling for “the androgynous minority” to organize as a political entity.

Hay’s call for an “international bachelor’s fraternal order for peace and social dignity” did not bear results until 1950. That year, his love affair with Viennese immigrant Rudi Gernreich (whose fashion designs eventually earned him a place on the cover of Time magazine), brought Hay into gay circles where a critical mass of daring souls could be found to begin sustained meetings. On November 11, 1950, at Hay’s home in the Silver Lake district of Los Angeles, a group of gay men met which became the Mattachine Society. Of the original Mattachine founders, Chuck Rowland, Bob Hull, and Dale Jennings pre-deceased Hay. Konrad Stevens and John Gruber are the last surviving members of the founding group.

“Mattachine” took its name from a group of medieval dancers who appeared publicly only in mask, a device well understood by homosexuals of the 1950s. Hay devised its secret cell structure (based on the Masonic order) to protect individual gays and the nascent gay network. Officially co-gender, the group was largely male — the Daughters of Bilitis, the pioneering lesbian organization, formed independently in San Francisco in 1956.

Though some criticized the Mattachine movement as insular, it grew to include thousands of members in dozens of chapters, which formed from Berkeley to Buffalo, and created a lasting national framework for gay organizing. Mattachine set the stage for rapid civil rights gains following 1969’s Stonewall riots in New York City.

Harry Hay was born in England in 1912, the day the Titanic sank. His father worked as a mining engineer in South Africa and Chile, but the family settled in Southern California. After graduating from Los Angeles High School, he briefly attended Stanford, but dropped out and returned to Los Angeles. He understood from childhood that he was a sissy — different in behavior from boys or girls — and also that he was attracted to men. His same-sex affairs began when he was a teenager, not long after he began reading 19th century scholar Edward Carpenter, whose essays on “homogenic love” strongly influenced his thinking.

A tall and muscular young man, Hay worked as both an extra and ghostwriter in 1930s Hollywood. He developed a passion for theater, and performed on Los Angeles stages with Anthony Quinn in the 1930s, and with Will Geer, who became his lover. Geer (who later generations grew to love as Grandpa Walton on the TV series “The Waltons”), took Hay to the San Francisco General Strike of 1934, and indoctrinated him into the American Communist Party. Hay became an active trade unionist. A blend of Marxist analysis and stagecraft strongly influenced his later gay organizing.

Despite a decade of gay life, in 1938 Hay married the late Anita Platky, also a Communist Party member. The couple were stalwarts of the Los Angeles Left. Hay taught at the California Labor School and worked on domestic campaigns like that for Ed Roybal, the first Latino elected in Los Angeles. The Hayses occasionally hosted Pete Seeger when he performed in Los Angeles, and Hay recalled demonstrating with Josephine Baker in 1945 over the Jim Crow segregation policy of a local restaurant. When he felt compelled to go public with the Mattachine Society in 1951, Hay and his wife divorced.

After a burst of activity lasting three years, the growing Mattachine rejected Hay as a liability due to his Communist beliefs. In 1955, when he was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee, he had trouble finding a progressive attorney to represent him. He felt this was due to homophobia on the Left. (He was ultimately dismissed after his curt, brief testimony was deemed unimportant.) Hay felt exiled from the Left for nearly fifty years, until he received the Life Achievement Award of a Los Angeles library preserving the history and artifacts of progressive movements.

A second wind of activism came in 1979 when Hay founded, with Don Kilhefner, a spiritual movement known as the Radical Faeries. This pagan-inspired group continues internationally based on the principle that the consciousness of gays differs from that of heterosexuals. Hay believed that this different way of seeing constituted the greatest contribution gays made to society, and was indeed the reason for their continued presence throughout history.

For most of his life Hay lived in Los Angeles. However, during the early 1940s, Hay and his wife lived in New York City. He returned there with John Burnside to march and speak at the Stonewall 25 celebration in 1994. During the 1970s, he and Burnside moved to New Mexico, where he ran the trading post at San Juan Pueblo Indian reservation.

His years of research for gay references in history and anthropology texts led Hay to formulate his own gay-centered political philosophy, which he wrote and spoke about constantly. His theory of “gay consciousness” placed variant thinking as the most significant trait in homosexuals. “We differ most from heterosexuals in how we perceive the world. That ability to offer insights and solutions is our contribution to humanity, and why our people keep reappearing over the millennia,” he often stressed.

Hay’s occasional exhortations that gays should “maximize the differences” between themselves and heterosexuals remained controversial. Some academics and activists seeking full integration of gays and lesbians into straight society tended to reject his ideas while still respecting his historic stature.

A fixture at anti-draft and anti-war demonstrations for sixty years, Hay worked in Women’s Strike for Peace during the Vietnam War as a conscious strategy to build a coalition between gay and feminist progressives. He also worked closely with Native American activists, especially the Committee for Traditional Indian Land and Life. Hay was a local founder of the Lavender Caucus of Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition during the early 1980s, and was determined to convince the gay community that its political success was inextricably tied to a broader progressive agenda.

Despite his often-combative nature, Hay became an increasingly beloved figure to younger generations of gay activists. He was often referred to as the “Father of Gay Liberation.”

Hay is survived by Burnside as well as by his self-chosen gay family, a model he strongly advocated for lesbians and gays. His adopted daughters, Kate Berman and Hannah Muldaven, also survive him. A circle of Radical Faeries provided care for him and Burnside through their later years.

Harry Hay leaves behind a wide circle of friends and admirers among lesbians, gays, and progressive activists. Donations in his memory can be made to the San Francisco GLBT Community Center, 1800 Market Street, San Francisco CA 94102 (identify it for the Harry and John Founders Wall plaque), or to the One Institute and Archives, 909 West Adams Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90007.

Birthday Statement and Obituary by Massimo Consoli

Frattocchie, 25 October 2002

I receive the news from Michael Lombardi-Nash that Harry Hay died the day before yesterday, October 23, Wednesday.

He was very old and his health conditions had now worsened; He hadn’t responded to my letters for a long time and I was a little prepared for this…

This doesn’t mean that his passing doesn’t make me feel great, great pain because of the extraordinary nature of his character, because of his almost symbolic value of what he is. was our movement and our community, for the very close relationship of friendship and affection that bound me to him.

Italians are not very familiar with Harry Hay, unfortunately, even though he was one of the fundamental pillars of the GLBT movement and community.

I have tried to talk about it as much as possible, in the belief that the cult of historical memory is the most effective tool for the affirmation of our freedom.

Last April 7, on the occasion of his 90th birthday, the Radicals of the Left had the intelligence and sensitivity to dedicate their first brunch in the new Roman headquarters to his celebration.

About ten years ago, on 29 March 1992, I proclaimed him “blessed” to “underline his extraordinarily positive influence both directly in the lives of many people and indirectly in the birth, development and diffusion of a gay movement which, in turn, is state and is a formidable instrument of moral, civil and cultural emancipation” .

Harry was very happy to be the first “living quasi-saint” in history and had T-shirts made with the “official” image of the beatification printed on them, taken from the holy card created by Enrico Verde and published in Rome Gay News. He had a humor that intertwined and blended very well with mine.

Here are two documents to help you get to know him a little better and the “saint” made in ’92 by Enrico Verde.

1. The statement for his birthday, April, 2002.

2. The article appeared in Guidemagazine N° 5, May 2002.

Next Sunday, 7 April 2002, is the 90th (ninetieth!!!) birthday of HARRY HAY, a character who is not very well known in Italy, but who is of fundamental importance for our history…

I was very lucky, in my life, and I have had the perhaps unique opportunity to meet, associate with and have friendships with almost all the most relevant actors in the contemporary gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender movement, both European and American.

HARRY HAY is one of these and, probably, the dearest one I have, given his extreme sweetness, his affable character, the strong sensitivity that characterizes him.

In ’93 a stormy wind blew through the Italian community. Some of my statements were misrepresented by some circles and newspapers and reported in a specious manner. I went through a long moment of depression which pushed me to significantly limit my activities.

There were even those who declared to the press that I couldn’t speak on behalf of the gay movement since… I wasn’t having sex anymore! (“Consoli … is the victim of his frustrations because he hasn’t made love for 5 years”, Il Tempo, 9 May 1993) .

The only voice that came to support me was certainly the most authoritative of all: that of the founder of the first GLBT association, the only one still alive, from which, in cascade, all the groups, circles and movements, initially American, emerged. but which then left their mark on the rest of the world: the voice of HARRY HAY.

Harry sent me one of his usual, very long letters (five pages long…), in which he retraced the history of homosexuality, from “tribal communities” to “bodily fluids”, from the “Old Testament” to “Faerie Meetings” , of which he was one of the organizers (he is the last supporter of Ulrichs’ “third gender” theory) … and all this to lift my spirits…

Massimo Consoli

2. Guidemagazine N° 5, May 2002-10-25

In Worthing, a seaside resort near London, Harry Hay was born on Easter Sunday 7 April 1912. He will become the founder of the modern gay movement.

Last April 7, 2002, a large part of the American movement met at the San Francisco LGBT Community Center to celebrate the 90th anniversary of this exceptional figure to whom we all owe something today.

THE BLESSED LIVING OF THE GAY

1948 is a year full of turmoil. The Forbundet was founded in Denmark in 1948 , in Sweden the Riksforbundet for Sexuellt Likaberattigande (RFSL) , in Norway the Norske Forbundet in 1948 : associations that are still alive and active today.

During that summer, on the coast of California, someone printed a flyer and distributed it to the numerous anonymous gays sunbathing on the beach. It is an appeal to support the candidacy for the White House of Henry Wallace, who was a minister and also vice-president under Truman, before being fired because he was too critical (from the left) of the administration.

The leaflet is signed by the International Fraternal Order for Peace and Social Dignity , but everyone will talk about it as Celibates Anonymous or Celibates for Wallace . The Order presents itself as “a service and assistance organization for the protection and improvement of the Androgynous Minority in Society”.

The idea for such an initiative came out during a gay party at the University of Southern California when, one beer after another, everyone tried to make it bigger than their neighbor. Among the participants is Henry Hay , nicknamed Harry , a cultural organizer of the communist party to which he has been a member for fifteen years, born in England in 1912, working at the party’s educational center in Los Angeles where he teaches “materialist development of music in history” and married to another militant, at the suggestion of a leader to whom he confided his homosexuality.

Harry Hay thinks about it for two years. The disappointment over Wallace’s failure is great. America prepares for the Korean War in the midst of a rising tide of paranoia against all that is not WASP, i.e. White, Anglo-Saxon and Protestant. In 1950, Senator Joseph McCarthy held his famous “Wheeling speech”, asking that the state administration be “purged” of the presence of subversives, in particular communists and inverts, but also of those who showed themselves “too sociable with black and unorthodox in dress, or has joined Wallace’s Progressive Party.

He begins a series of investigations in federal offices, then in the army and finally against important cultural figures.

Hay understands that one of the periodic persecutions has begun where gays have the historical function of scapegoats. He talks to the homosexual students in his music class, almost all of them communists or ex-communists, arguing the need for an organization that fights for their rights.

On July 20, 1951, his efforts were crowned with success and he founded the Mattachine Society . The name was inspired by those musical societies which, in medieval and Renaissance Mediterranean Europe, were composed of “celibate citizens who never performed in public without a mask” .

These citizens, during the winter equinox, moved to the countryside to celebrate their rites.

His Mattachine was born “To unify those homosexuals isolated from their own kind […] To educate homosexuals and heterosexuals to an ethical homosexual culture [. . .] parallel to the cultures emerging from our minority brothers: the blacks, the Mexicans , the Jews […] To direct the most socially conscious homosexuals towards leadership of the entire mass of social deviants […] To assist our people who are daily victimized as a result of our oppression […]”

The first document is a petition against US involvement in Korea. Signatures are collected, once again, along the gay beaches of Southern California.

In 1952 Mattachine made itself known to the general public through an amazing initiative. The Los Angeles police, following a deplorable practice consolidated in the United States and which has a long tradition in Anglo-Saxon countries, “traps” Dale Jennings, having him lured to a cruising spot by a young, handsome and somewhat slutty officer.

Dale is one of the founders and among the most combative. He has no intention of suffering as gays have always suffered up to that point. He consults with his friends and, together, they decide to create a Citizens Committee to Outlaw Entrapment. They distribute flyers in bars and along gay beaches and, at the trial, Dale denies having made any “proposals” to the policeman, but admits to being homosexual. His courage shocks the jury who no longer knows which way to turn and the Public Prosecutor ends up withdrawing the accusation.

Victory is a formidable advertising tool. In 1953 there were already more than one hundred groups connected to the Mattachine, with participation exceeding two thousand units.

The structure of the organization is “secret, hierarchical, cellular”, with five orders of membership arranged in a pyramid. The leaders are at the fifth level and the great mass of members of the other cells below and separated from each other do not know who they have above or next to them…

In times closer to our own, Harry Hay has been busy developing his theory of the “Third Gender” , very close to that of Ulrichs ‘ “Third Sex” , and in organizing the “Faeries” , the “Fairies” close to nature, to ecology, which are one of the liveliest components of the American GLBT movement.

Massimo Consoli

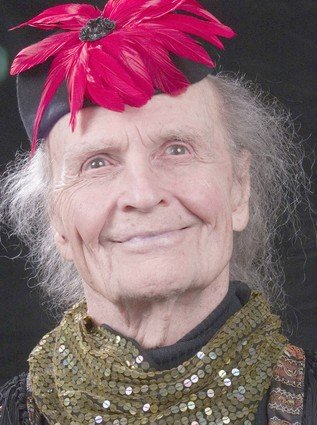

John Burnside

Gay Activist and a Founder of the Radical Faeries

November 2, 1916 – September 14, 2008

John Lyon Burnside III, 1916-2008

photo by Rory Cecil

Harry and John at Gay Pride SF

photo by Peridot

Los Angeles Times

September 18, 2008 http://articles.latimes.com/2008/sep/18/local/me-burnside18

John Burnside dies at 91;

Gay rights activist, teleidoscope inventor

By Dennis McLellan, Los Angeles Times Staff Writer

John Burnside, the inventor of a kaleidoscope-like device called the teleidoscope and an early gay movement activist who was the longtime partner of the late gay rights pioneer Harry Hay, has died. He was 91.

Burnside, who had recently been diagnosed with glioblastoma brain cancer, died Sunday at his home in San Francisco, said Joey Cain, a longtime friend.

“I don’t think it’s a cliche to say that John Burnside epitomized the full meaning of the word gentleman,” said Mark Thompson, a well-known writer on gay history and culture who knew Burnside for nearly 30 years. “He was not only smart and funny and bright, he was also profoundly, at his core, a gentle man and all that that implies.

“He was a very beloved person in our community of men loving men.”

A onetime staff scientist at Lockheed, Burnside had an interest in optical engineering that led to his inventing the teleidoscope, a variation on the kaleidoscope that works without the use of colored glass chips and instead uses a lens to transform whatever is in front of it into a colorful design.

In 1958, he launched California Kalidoscopes, which became a successful Los Angeles design and manufacturing plant.

In the 1970s, Burnside created the Symetricon, a large mechanical kaleidoscopic device that projects colorful patterns; it was used in a number of movies, including the 1976 science fiction film “Logan’s Run.”

By then, Burnside was more than a decade into what would be a 39-year relationship with Hay, who had started the pioneering Mattachine Society, a gay rights organization, in Los Angeles in 1950.

When they first met at a gay community center in downtown Los Angeles in 1963, Burnside was married with no children. He divorced his wife and moved in with Hay.

The two men became a highly visible activist couple, including appearing together on confrontational TV talk show host Joe Pyne’s program.

In 1965, Burnside and Hay helped form the Southern California Council on Religion and the Homophile.

A year later, they participated in one of the country’s first gay rights demonstrations: a 15-car motorcade through downtown Los Angeles protesting the exclusion of gays from the military.

And in 1969, they participated in the founding meetings of the Southern California Gay Liberation Front, one of which was held at Burnside’s teleidoscope factory.

“They were real role models for positive gay life, and they were activists who put their lives literally on the line in countless demonstrations, marches and parades,” Thompson said.

But Hay and Burnside weren’t committed just to gay issues, he said. “They were totally committed to peace and justice issues on a wide spectrum of social concerns, including Native American rights, women’s and labor issues, fair employment and housing — they were just good social activists.”

In 1970, Burnside and Hay moved to San Juan Pueblo, N.M.

“They had gone out there to help Native Americans reclaim their water rights,” said Don Kilhefner, co-founder of the Los Angeles Gay & Lesbian Center. “They were a very socially and politically conscious couple. You couldn’t ask for better.”

In 1979, Burnside and Hay joined Kilhefner in organizing the first Spiritual Gathering for Radical Faeries, a weekend get-together in a remote ashram east of Tucson.

The Radical Faeries, which Kilhefner said began as a gathering of about 150 gay men to bring a new level of consciousness and spirituality to the gay liberation movement, has grown into an international movement.

Burnside and Hay were featured in the 1977 documentary “Word Is Out,” and they appeared together in the 2002 documentary about Hay, “Hope Along the Wind.”

John Lyon Burnside III was born in Seattle on Nov. 2, 1916. He joined the Navy at 16 and married soon after his discharge.

A 1945 graduate of UCLA, where he studied physics and mathematics, Burnside launched his career in the aircraft industry.

Burnside and Hay moved back to Los Angelesfrom New Mexico in 1979.

They moved to San Franciscoin 1999 and continued their activist work; Hay died in 2002 at age 90.

Donations in Burnside’s memory to continue his and Hay’s activist work may be made to the Harry Hay Fund, c/o Chas Nol, 174 1/2 Hartford St., San Francisco, CA 94114.

Bay Area Reporter [San Francisco, CA]

September 18, 2008 https://www.ebar.com/news///239330/john_burnside_dies_at_91

John Burnside dies at 91

Veteran Queer Activist Radical Faerie

by Liz Highleyman

John Burnside greets the crowd after being acknowledged from the stage during the dedication of the Harvey Milk bust in San Francisco City Hall on May 22. Photo: Rick Gerharter

John Lyon Burnside III, an inventor, dancer, and activist, died Sunday, September 14. Recently diagnosed with glioblastoma brain cancer, he passed away surrounded by loving friends at the age of 91.

Mr. Burnside was perhaps best known as the life partner of Harry Hay, who started the first U.S.gay rights organization, the Mattachine Society, in 1950. Having lived in the Castro since 1999, Mr. Burnside resided for the past several months at the Haight-Ashbury home of former Pride board president Joey Cain.

“It was a blessing for all of us to have John in our lives,” Cain said. “He was so beloved by the community. He just exuded warmth and joy, and he had a dead-on fashion sense.”

“He was an amazing human being, he was magical, he was fairy dust, and he was a stalwart early pioneer of LGBT human rights,” said Assemblyman Mark Leno (D-San Francisco), who met Mr. Burnside shortly before Mr. Hay’s death in 2002.

Mr. Burnside was born November 2, 1916, in Seattle. An only child, he was raised by his mother after his father left the family; being poor, she periodically placed her son in the care of orphanages.

Mr. Burnside joined the Navy at age 16. Soon after his discharge, he settled in Los Angeles and married Edith Sinclair; the couple had no children. He studied physics and mathematics at theUniversity of California at Los Angeles, graduating in 1945. He pursued a career in the aircraft industry, including a stint as a staff scientist at Lockheed.

Mr. Burnside’s interest in optical engineering led him to invent the teleidoscope, a type of kaleidoscope that works without colored glass chips. He received a patent on the device, which brought him considerable income. In 1958, he started his own company, California Kaleidoscopes. He later created the symetricon, a large kaleidoscopic device that projects patterns, which was used in several Hollywood films.

Mr. Burnside began coming to terms with his attraction for men in the 1960s. Some gay workers at the kaleidoscope workshop told him about the ONE Institute, and he began attending classes. There, in 1963, Mr. Burnside (then age 47) met Mr. Hay (then 51), who was promoting a gay square dancing group. The two embarked on a whirlwind romance that led to Mr. Burnside divorcing his wife and moving in with Mr. Hay.

Together, Mr. Burnside and Mr. Hay participated in many of the key events of the burgeoning gay movement. In May 1966, they were part of a 15-car motorcade through downtown Los Angeles to protest the military’s exclusion of homosexuals. In 1969, they attended the founding meetings of the Southern California Gay Liberation Front. Although Mr. Burnside had not been an activist before meeting Mr. Hay, the two men became fixtures at pickets and demonstrations supporting labor and the anti-war movement, as well as gay rights.

“John was always so inquisitive and had so many interests politics, the environment, social justice, history, science, engineering, the arts he could engage anyone in meaningful conversation,” said Mr. Hay’s niece, Sally Hay, a lesbian activist in Rhode Island who worked at Mr. Burnside’s kaleidoscope factory as a college student in 1969. “To the very end, he lived his life with great enthusiasm.”

In 1970, Mr. Burnside and Mr. Hay moved to San Juan Pueblo, New Mexico, drawn by their involvement in the Indian Land and Life Committee and Mr. Hay’s growing interest in Native American culture, in particular the two-spirit people. Like Mr. Hay, Mr. Burnside came to see gay people as a distinct group with a particular role in society. “The crown of gay being is a way of loving, of reaching to love in a way that far transcends the common mode,” he wrote in 1989.

In 1979, frustrated with the gay movement’s drift toward mainstream assimilation, Mr. Burnside and Mr. Hay, along with fellow activists Don Kilhefner and Mitch Walker, organized the first Spiritual Gathering of Radical Faeries. Since that first gathering of 200 men at an ashram near Tucson, the faerie movement has held dozens of gatherings around the world and established permanent sanctuaries across the country. “The people who have come to the gatherings came looking to find themselves,” Mr. Burnside once said, “but they found each other, too.”

Mr. Burnside and Mr. Hay were among the first long-term gay male couples in the public eye, and thus served as role models for countless LGBT people. As early as 1967, they appeared together on the Joe Pyne television show in Los Angeles. They were featured in the groundbreaking 1977 documentary Word is Out, as well as the 2002 biographical documentary Hope Along the Wind.

“People mostly remember him as Harry Hay’s partner, but John was his own very powerful and very creative person,” said Hope Along the Wind director Eric Slade. “He was a deep thinker and a beautiful man.” Slade said he plans to incorporate hours of additional footage of Mr. Burnside into a feature for the DVD release of the film.

In 1999, Mr. Burnside and Mr. Hay came to San Francisco, where Mr. Hay had been selected as grand marshal of that year’s Pride parade. After Mr. Hay became too ill to return to Los Angeles, friends helped the couple to relocate to the city. Mr. Burnside became a familiar presence, never missing the weekly Faerie Coffee Circles at the LGBT Community Center after it opened.

Although they maintained a loving partnership for nearly 40 years, Mr. Burnside and Mr. Hay had an open relationship and expressed no interest in legal marriage. In a 1989 Valentine to Mr. Hay, Mr. Burnside wrote, “Hand in hand we walk, as wing tip to wing tip, our spirits roam the universe, finding lovers everywhere.”

“John and Harry, along with Del [Martin] and Phyllis [Lyon], symbolized for a whole generation the possibility that two gay people could sustain a committed, long-term loving relationship,” said Cain. “However, John had no interest in imitating the heteros in any way, and marriage was for him an unimaginative institution of the oppressor. He believed that gay people would create new forms of relations that were suited to their unique ways of loving one another.”

Indeed, Mr. Burnside and Mr. Hay created around themselves a broad community of friends, lovers, and supporters. A group of Radical Faeries dubbed the Circle of Loving Companions cared for the two men during their final years.

“His life dispelled the notion that haunted all the early LGBT freedom fighters, that without the hetero family structure you will die lonely and unloved,” Cain added.

“John Burnside’s gifts to queer life are deep and powerful,” said GLBT Historical Society board member Terence Kissack. “His love for art, justice, and the beloved communities he helped nurture continue to inspire. I am particularly grateful for the way he helped take a word, ‘fairy,’ that has cut so many of us to the quick and made it a living symbol of joy, freedom, and fellowship.”

A spontaneous memorial altar for Mr. Burnside has been set up at the corner of 18th and Castro streets. A public memorial service is being planned. In accordance with his wishes, Mr. Burnside’s ashes will be co-mingled with those of Mr. Hay and scattered at the Nomenus Radical Faerie Sanctuary in Wolf Creek, Oregon.

Donations in Mr. Burnside’s memory may be made to the Harry Hay Fund, which will continue their work toward gay liberation. The Harry Hay Fund, c/o Chas Nol, 174 1/2 Hartford Street, San Francisco,CA 94114.

Gay Wisdom blog

September 16, 2008 http://whitecrane.typepad.com/gaywisdom/2008/09/rest-in-peace-.html

Rest In Peace – John Burnside

John Burnside 1916 – 2008

It is just incredibly sad to announce that John Burnside, Harry Hay’s lifetime partner, has passed, peacefully in San Francisco, surrounded by the circle of Radical Faeries who have taken care of him since Harry passed.

John Lyon Burnside III

November 2, 1916 – September 14, 2008

John Lyon Burnside III passed away peacefully at the age of 91 in this home on Sunday, September 14 surrounded by the Circle of Loving Companions who had been caring for him. He had been recently diagnosed with glioblastoma brain cancer.

John was an activist, inventor, dancer, physicist, a founder of the Radical Faeries, and partners for nearly 40 years with Harry Hay. Hay started the Gay rights organization the Mattachine Society in 1950 and is considered a founder of the modern gay freedom movement.

John Burnside was born on November 2, 1916 and was an only child . He joined the Navy at age 16. Soon after his discharge he was married to Edith Sinclair.

He studied physics and mathematics at UCLA, graduating in 1945. John pursued a wartime career in the aircraft industry, eventually securing a job at Lockheed as a staff scientist.

His interest in optical engineering lead to his invention of the teleidoscope, an innovative variation on the kaleidoscope that works without the traditional glass chips to color the view. Instead it turns whatever is in front of its telescopic viewfinder into a symmetrical mandala. His patent on the device allowed him in 1958 to drop out of mainstream society and set up the California Kalidoscopes in Los Angeles which soon became a successful design and manufacturing plant. The teleidoscope was sold in stores across the country and was featured in the Village Voice.

John continued his optical innovations in the 1970s, creating the Symetricon, a large mechanical kaleidoscopic device that projects intricate, colorful patterns. Images from the symetricon were used in a number of Hollywood films, including Logan’s Run.

It was in 1963 that John made perhaps the biggest change of his life. After befriending Gay workers at his teleidoscope factory he learned of the ONE Institute, a Gay community center in downtown Los Angeles. While attending a seminar at ONE in September of that year he met Harry Hay. The two began a whirlwind romance and, after divorcing Edith, John moved in with Harry.

Together John and Harry were involved in many of the Gay movement’s key moments. In May of 1966 the two were part of a 15 car motorcade through downtown Los Angeles protesting the military’s exclusion of homosexuals. The event is considered one of the country’s first gay protest marches.

John and Harry appeared as a Gay couple on the Joe Pyne television show in Los Angeles in 1967, two years before the Stonewall riots in New York. In 1969 they participated in the founding meetings of the Southern California Gay Liberation Front, which met in John’s teleidoscope factory.

Drawn by Harry’s lifelong interest in Native American culture and a shared involvement with the Indian Land and Life Committee, they moved to San Juan Pueblo, New Mexico in 1970. While there, John and Harry were interviewed for the groundbreaking Gay documentary Word is Out. John was honored at the Frameline GLBT Film Festival in San Francisco this year during the 30th anniversary screening of the film. He was also featured in Eric Slade’s 2002 documentary film about Hay, Hope Along the Wind.

In 1979 John and Harry joined with fellow activists Don Kilhefner and Mitch Walker to call the first Spiritual Gathering of Radical Faeries. Fed up with the Gay movement’s steady drift towards mainstream assimilation, the gathering called to Gay men across the country. Since that time dozens of Faerie gatherings have been called around the world and permanent Radical Faerie sanctuaries have formed across the country. The movement helped to nurture and create a specifically Gay centered spiritual exploration and tradition.

John published a short essay in 1989 titled “Who are the Gay People?”, that helped explain his views of Gay people’s role in the world. John writes, “The crown of Gay being is a way of loving, of reaching to love in a way that far transcends the common mode.”

In 1999 John and Harry moved to San Francisco where they continued their activist work. A group of Radical Faeries, the Circle of Loving Companions, became caretakers for the two of them. Harry Hay died in 2002 at the age of 90. The two had been together for 39 years.

In a 1989 Valentine to Harry, John Burnside wrote, “Hand in hand we walk, as wing tip to wing tip our spirits roam the universe, finding lovers everywhere. Sex is music. Time is not real. All things are imbued with spirit.”

John was a familiar and much loved presence in San Francisco’s LGBT Community. He rode every year, including this last, in the San Francisco LGBT Pride Parade. He never missed a single Faerie Coffee Circle held each Saturday in San Francisco’s LGBT Community Center.

Speaking for the Circle of Loving Companions, John’s friend of 27 years, Joey Cain said:

“We are saddened by our dear, sweet John’s passing, but are gratified that John’s last years were happy and he was surrounded by people who loved him. His life dispelled the notion that haunted all the early LGBT freedom fighters, that without the hetero family structure you will die lonely and unloved. The work that John, Harry and the other LGBT pioneers did has dispelled that destiny forever for all of us.”

Donations in John’s honor may be made to the Harry Hay Fund, to continue the activist work of John Burnside and Harry Hay. Donations may be sent to:

The Harry Hay Fund

c/o Chas Nol

174 ½ Hartford Street

San Francisco, CA 94114

San Francisco Bay Times

September 18, 2008 http://sfbaytimes.com/?sec=article&article_id=9021

John Burnside Passes

Veteran Queer Activist Radical Faerie

by Sister Dana Van Iquity

A memorial shrine to John Burnside sprang up at 18th and Castro, on news of his death. Photo by Rink.

John Lyon Burnside III passed away peacefully at the age of 91 in this home on Sunday, September 14 surrounded by the Circle of Loving Companions who had been caring for him. He had been recently diagnosed with glioblastoma brain cancer. Burnside was an activist, inventor, dancer, physicist, a founder of the Radical Faeries, and partner for nearly 40 years with Harry Hay. Hay started the gay rights organization, the Mattachine Society, in 1950 and is considered a founder of the modern gay freedom movement.

Burnside was born on November 2, 1916 and was an only child. He joined the Navy at age 16. Soon after his discharge, he was married to Edith Sinclair. He studied physics and mathematics at UCLA, graduating in 1945. He pursued a wartime career in the aircraft industry, eventually securing a job at Lockheed as a staff scientist.

His interest in optical engineering led to his invention of the teleidoscope, an innovative variation on the kaleidoscope that works without the traditional glass chips to color the view. Instead it turns whatever is in front of its telescopic viewfinder into a symmetrical mandala. His patent on the device allowed him in 1958 to drop out of mainstream society and set up the California Kaleidoscopes in Los Angeles, which soon became a successful design and manufacturing plant. The teleidoscope was sold in stores across the country and was featured in the Village Voice. He continued his optical innovations in the 1970s, creating the symetricon, a large mechanical kaleidoscopic device that projects intricate, colorful patterns. Images from the symetricon were used in a number of Hollywood films, including Logan’s Run.

It was in 1963 that John made perhaps the biggest change of his life. After befriending gay workers at his teleidoscope factory, he learned of the ONE Institute, a gay community center in downtown Los Angeles. While attending a seminar at ONE in September of that year, he met Harry Hay. The two began a whirlwind romance and, after divorcing Edith, Burnside moved in with Hay.

Together they were involved in many of the gay movement’s key moments. In May of 1966, the two were part of a 15-car motorcade through downtown Los Angeles protesting the military’s exclusion of homosexuals. The event is considered one of the country’s first gay protest marches.

They appeared as a gay couple on the Joe Pyne television show in Los Angeles in 1967, two years before the Stonewall riots in New York. In 1969, they participated in the founding meetings of the Southern California Gay Liberation Front, which met in Burnside’s teleidoscope factory.

Drawn by Burnside’s lifelong interest in Native American culture and a shared involvement with the Indian Land and Life Committee, they moved to San Juan Pueblo, New Mexico in 1970. While there, they were interviewed for the groundbreaking gay documentary Word is Out. Burnside was honored at the Frameline LGBT International Film Festival in San Francisco this year during the 30th anniversary screening of the film. He was also featured in Eric Slade’s 2002 documentary film about Hay, Hope Along the Wind.

In 1979, the couple joined with fellow activists Don Kilhefner and Mitch Walker to call the first Spiritual Gathering of Radical Faeries. Fed up with the gay movement’s steady drift towards mainstream assimilation, the gathering called to queer men across the country. Since that time, dozens of Faerie gatherings have been called around the world, and permanent Radical Faerie sanctuaries have formed across the country. The movement helped to nurture and create a specifically gay-centered spiritual exploration and tradition.

Burnside published a short essay in 1989 titled “Who Are the Gay People,” that helped explain his views of queers’ role in the world. Burnside wrote, “The crown of gay being is a way of loving, of reaching to love in a way that far transcends the common mode.”

In 1999, the couple moved to San Francisco, where they continued their activist work. A group of Radical Faeries, the Circle of Loving Companions, became caretakers for the two of them. Harry Hay died in 2002 at the age of 90. The two had been together for 39 years. In a 1989 Valentine to Hay, Burnside wrote, “Hand in hand we walk, as wing tip to wing tip our spirits roam the universe, finding lovers everywhere. Sex is music. Time is not real. All things are imbued with spirit.”

Burnside was a familiar and much loved presence in San Francisco’s queer community. He rode every year, including this last, in the SF LGBT Pride Parade. He never missed a single Faerie Coffee Circleheld each Saturday in the LGBT Community Center.

“We are saddened by our dear, sweet John’s passing, but are gratified that John’s last years were happy, and he was surrounded by people who loved him,” Burnside’s friend of 27 years, Joey Cain, speaking for Circle of Loving Companions, said. “His life dispelled the notion that haunted all the early LGBT freedom fighters – that without the hetero family structure, you will die lonely and unloved.” Cain added, “The work that John, Harry, and the other LGBT pioneers did has dispelled that destiny forever for all of us.”

Donations in Burnside’s honor may be made to the Harry Hay Fund, to continue the activist work of John Burnside and Harry Hay. Donations may be sent to The Harry Hay Fund, c/o Chas Nol, 174 ½ Hartford Street.

Gay City News [New York, NY]

September 18, 2008

John Burnside, Gay Pioneer, Dies

by Jason Victor Serinus

John Lyon Burnside III, longtime partner of Mattachine Society founder Harry Hay, died peacefully in San Francisco on September 14 at the age of 91. The cause of death was an extremely aggressive form of glioblastoma brain cancer. Hay, who many consider the founder of the modern gay liberation movement, died in 2002 at the age of 90 from a tumor in the lungs.

At the time of his passing, Burnside was surrounded by members of the Circle of Loving Companions. The group, whose name derives from a non-profit Burnside and Hay founded in the 1960s, re-formed in 1999 when the couple moved to San Francisco in order to receive round-the-clock support and care.

John Burnside was an activist, inventor, dancer, physicist, and lover of men. He and Harry Hay became a couple in 1963, more than a decade after Harry founded the Mattachine Society in 1950. They were part of a generation of lesbian and gay elders, including Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, who founded the LGBT movement. In 1979, together with Don Kilhefner and Mitch Walker, they convened the first Spiritual Gathering of Radical Faeries.

By appearing in the landmark 1977 gay documentary “Word is Out,” John and Harry gave hope to generations of lesbians and gays that gay couples can form in their mature years and survive into old age. Burnside was honored at the Castro Theater this year during the 30th anniversary screening of the film. He was also featured in Eric Slade’s 2002 documentary film about Hay, “Hope Along the Wind.”

“We know John had a joyful end,” said Circle member and former San Francisco Pride Parade president Joey Cain. “In his last years, he was surrounded by people who loved him. He knew he had that love. Let’s face it; the great bugaboo of gay men’s lives is that when they grow old, they will die alone, without the support of the family structure. What John and Harry created continues to help dispel that destiny for themselves and for all of us.”